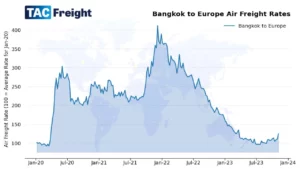

The outlook for inflation and interest rates continues to generate lots of debate in markets right now. Central banks, led by the US Federal Reserve, hit the pause button after a long and steep series of rate hikes in September – leading many to suggest we may be near the top of the hiking cycle. Indeed, some optimists suggest that with inflation dropping there could be room for rates to fall again next year. On the other hand, plenty of others have been pointing out that core inflation looks pretty sticky – which may mean rates need to stay ‘higher for longer’ in order to quell it decisively. Meanwhile, geopolitical stresses were ratcheted up further in the past month by events in Israel and Gaza – adding to the war already happening in Ukraine, plus tensions over Taiwan. Events in Gaza should only impact air cargo if that war spreads across the Middle East – which might mean some aircraft taken off the commercial market. Against that troubled backdrop, the oil price – which spiked then eased after Saudi Arabia cut production in September – spiked then eased again in October. Some commentators see the oil market as ‘tight’ – thus prone to a further big jump if tensions in the Middle East escalate. Others, however, point to rising US shale production plus higher sales of oil from Iran – and Russia successfully circumventing sanctions – to argue the market shouldn’t have too much further upside from here. In the midst of all this, global air freight rates maintained a firm tone during the month. The overall Baltic Air Freight Index (BAI00) was up another +2.9% over the four weeks to 30 October. Although the index was still down -30.2% from 12 months earlier, that clocks up a second successive monthly again – after an +11% rise in September – adding evidence of a genuine if modest peak season bounce this year. Sources suggest the firmer tone should continue as forward bookings look strong not just through the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday seasons but all the way to Chinese New Year. The rising trend has been led by rates out of southern China, with the index of outbound Hong Kong routes (BAI30) up another +11.6% in October, leaving it lower by only -16.4% YoY. Market activity continued to be led by e-commerce, with some forwarders said to be scrambling for capacity at rising spot prices – having failed to secure it previously through forward contracts and block space agreements (BSAs). It was led initially by strong demand on TransPacific routes to North America – where consumers have kept spending, despite running down their savings – though with rates to Europe also rising. The index for outbound Shanghai routes (BAI80) was also up, gaining +6.4% in October to leave it lower by only -22.0% YoY. Rising spot market activity was particularly visible out of Vietnam, from where rates spiked sharply during October both to Europe as well as to North America. A new route added to the data, from Bangkok to Europe, also rose in late October. Out of Europe, the market remained much weaker. Outbound Frankfurt (BAI20) was -3.0% in October, leaving it lower by -44.3% YoY. And London (BAI40) was -12.4% MoM, leaving it languishing at -59.2% YoY. Out of the Americas, the data on outbound rates from Chicago (BAI50) showed a lot of short-term gyrations week to week, but over the month were also lower – to leave the YoY figure at -42.5%. As noted in previous months, the performance of equities this year has been skewed towards a handful of mega tech stocks in the US – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – leaving the rest of the market pretty much flat to down. During the more recent market sell-off over the past couple of months, airline stocks have been among those hit. This seems strange given the three largest airlines in the US, for instance – United, American and Delta – have all posted increases in overall operating revenues so far this year. Despite falls of 30% or more in their air cargo revenues for Q3 compared with last year, all three airlines were benefitting from increased passenger traffic and load factors. And it seems hard to imagine their cargo revenues will fall much further – indeed, cargo volumes have been holding up well. In Europe, meanwhile, markets have been particularly depressed by side effects of the Ukraine war – with little or no growth in Germany dragging down the European economy as a whole as it has had to adjust away from over-reliance on Russian gas. That said, the European economy has indeed adjusted impressively, with gas consumption now down some 20% since the Ukraine conflict began – and overall power consumption down 10%. These are very significant savings given that overall economic activity has hardly shrunk if at all. Some suggest therefore that European stocks could be significantly undervalued compared with the US – and may offer a lot of upside from here. In Japan, meanwhile, the process of ‘normalisation’ of interest rates – after decades of low to negative rates and QE – is still in its early stages. But with underlying inflation now edging up, investors are gearing up for potential opportunities – especially in financial sector stocks. In air cargo specifically, shippers and carriers will both have been watching carefully the gyrations of the oil market. So far, however, recent spikes in crude oil have not fed through much to the jet fuel market – given a contraction of the ‘crack spread’. According to Platt’s data, the Brent crude price was lower by 4.4% over the month to 27 October. But jet fuel prices actually fell an average of 9.4% over the same period, given the expected easing of passenger demand as the winter season approaches. So the outlook for air cargo demand looks positive and the outlook for capacity and jet fuel prices doesn’t too scary